'Beyond Reason', published in water[shed]

Wilderness. Love. Photographer Peter Dombrovskis said you could live your whole life without either one, just so long as you never knew they existed.

But … if you did?

Close your eyes and conjure a Dombrovskis-style image. Perhaps composed of a pair of twined branches that whorl and twist around the emptiness left behind by love and wilderness in a heart that knew both.

Maybe the hollow would take the shape of Lake Pedder.

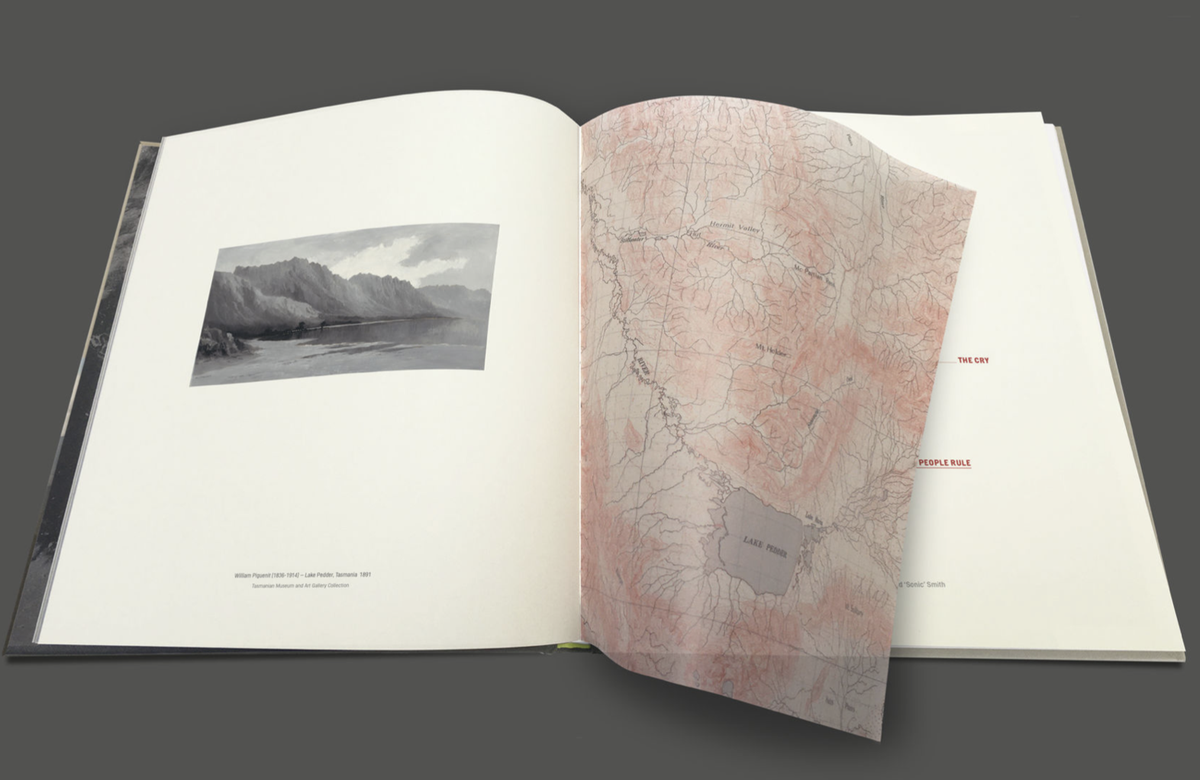

I never saw the lake. By the time I was born, in August of 1972, it was already drowning. With the Huon and the Serpentine rivers paralysed, the mountain ranges could do nothing but channel water down into a steadily filling basin. Every rainfall of that winter, every snowfall, became a layer of destruction.

Of those of us who never had the chance to see the lake, but love it regardless, it might be said that our love is second-hand, sparked by the mediated experience of paintings and photographs, the words of poets, activists and essayists, the expressions on the faces of our elders.

To say that we have fallen in love with a lake made of paint and pixels, of stories and sorrow, would not be unfair. In fact, it would be a tribute to the Pedder People and their long campaign to keep the lake alive in the collective imagination. Although the work they did in the 1960s and 1970s did not save the lake from inundation, it may yet transpire that their original outpourings of images, words and passion will play a critical role in the lake’s future.

The feelings of the younger generations of Pedder lovers are not strange, or unprecedented. Many writers over the years have expressed the sentiment that Carson McCullers captured this way: ‘We are homesick most for the places we have never known’.

The German language gave birth to the word fernweh (literally, ‘far sickness’) to describe a person’s longing for a place, or time, they have never visited, while Welsh speakers have the complex word hiraeth (literally, ‘long sorrow’) to express a longing for a person, place or time that is now unattainable, and the Portuguese language has given the world the word saudade, which poet Teixeira de Pascoaes defined as ‘desire for the beloved thing, made painful by its absence’.

Is what we feel for a lake, 50 years drowned, fernweh? Or is it hiraeth? Or perhaps saudade? Being neither German, Welsh nor Portuguese, I cannot say. Shut into the tower of my only language, I’m deaf to cultural subtleties they doubtless carry, blind to the textured layers of meaning that they must – with time and use – have accrued. Some have suggested that to feel hiraeth is not only to suffer the grief of loss, but also to hold the key to that grief’s redemption. I don’t know if that’s true. All I can say of fernweh, hiraeth and saudade is that they demonstrate the human need for words to communicate a potent blend of grief, nostalgia, longing, pleasure, regret, loss and desire.

What I think is true about Lake Pedder, for those of us fortunate enough to have known both love and wilderness, is that while the pictures and stories of those who went before us have informed us, educated us, and shown us precisely what missing from the south-west of this island, it is from our own experiences, and because of what we keep in our hearts, that we know why the absence of the lake matters.

Not often, but more than once and always while in a wild place, I have felt a powerful feeling that has no name. Sometimes, in the face of the mysterious, the deeply beautiful or the overwhelmingly terrible, we tell ourselves that ‘there are no words’. But it’s an idea that I – a wordsmith – resist. Surely it isn’t that there are no words, only that it might take time and patience to extract them from the bright seam of lived experience, to forge them from the raw material of life, to settle on the precise ones, to craft their combinations.

This was my feeling: that the wild place had ceased to be wild. Not that it had been tamed, but that it was not a place upon which I was intruding. It was not even a place I was observing, because I was no longer outside of it, but part of it. The foliage was not rough or alien, but comfortable. Even homely. The great distances I could see no longer seemed vast, nor impressive, because such concepts were irrelevant. Everything was simply right. Time, too, had disappeared. Or at least become blissfully unimportant. I might have been in any moment of the past, present or future. To be honest, I’m not sure I was any longer myself.

Though Kevin Kiernan wrote about his feeling for Lake Pedder in entirely different terms, I nevertheless suspect my feeling to have been a cousin to it. In the heartbreaking essay, ‘I Saw My Temple Ransacked’, he gave it these words:

I have loved many of the wild places it has been my good fortune to glimpse. But only at Lake Pedder did I feel somehow loved in return. The feeling flowed through me as I watched a sou’west storm wreathe the summits of the Frankland Range with mist then turned gold with the setting sun. It flowed through me as I stood upon the sand by Maria Creek while beach and water reflected the moonlight back into the night.

If you know that transcendence is possible, if you know that now and then a wild place can take you to another plane of existence, if you believe that a lake can love you in return, then it will be no mystery to you that Lake Pedder bewitched so many. While the lake was drowned, the evidence was not. Pedder, for many people, was a kind of portal. And this is why, even if we never had the chance to go there, we want to have it back.

Don’t imagine that I’m unaware that talk of this kind makes some people roll their eyes. I know that there are some who will find what I have to say sentimental and naïve. There are those who will be vastly more interested in the practicalities of decommissioning dams, or to know the value – in tourist dollars and jobs created and power generation capacity lost – of the lake’s restoration.

In the months and years ahead of us, science will continue to explain how we might get our lake back. Politics will continue to debate it. Economics will continue to work the figures. But art? Art will lay down the shield of reason and step out from behind it, vulnerable and naked. It will say ‘this how we feel’. It will illustrate, in a thousand different ways, without recourse to figures, why it is that we fight for the precious, natural places of the world to be left alone, respected, restored. Art will speak on behalf of our hearts. On behalf of the wilderness. And love.