'What is a prose poem? There is no consensus on a definition, but a widely loved explanation comes from Michael Benedikt, who suggests prose poetry is 'a genre of poetry, self-consciously written in prose, and characterised by virtually all the devices of poetry'. My own (much more prosaic) definition is this: 'prose poems are what prose writers create when they are struck by the lyric impulse, but too chicken-shit to do line-endings'.

I love poetry. Perhaps too much. I love it with a reverence that makes me nervous about writing it. Prose poetry feels like a safe compromise. It enables me to write a short thing in which I capture a moment or a feeling, or just a fragment of a story, without being forced to battle the demon of the line-ending: a mysterious act of severance and joining that some part of me believes to be the exclusive domain of real poets.

Intending to remain resolutely in the world of the prose poem, I began a residency at the Maritime Museum of Tasmania with a work called 'Here Passed Your Head', addressed to sea captain and novelist Joseph Conrad, whose only command was the Otago, the scuppered wreck of which gave its name to the Hobart suburb where I live. I imagined 'Here Passed Your Head' would be printed out on a bit of paper and pinned to the wall somewhere near the lovingly restored teak hatch cover, salvaged from the Otago, which rests in a prominent place in the museum's main gallery. Soon, however, I found myself transferring images of the solemn face of young Conrad onto calico, and stitching the words of my prose poem around it.

Several of the works I created for the residency ended up having textile counterparts: a knitted scarf spelled out a poem ('Row, Row, Row, Row') for Dinah Wilson and the convict-built dinghy she rowed around the vicinity of Cygnet and Gardners Bay for most of her married life; a cross-stitch, embellished with beach-combed seaweed, responded to the launch and the wreck of the ore carrier Lake Illawarra.

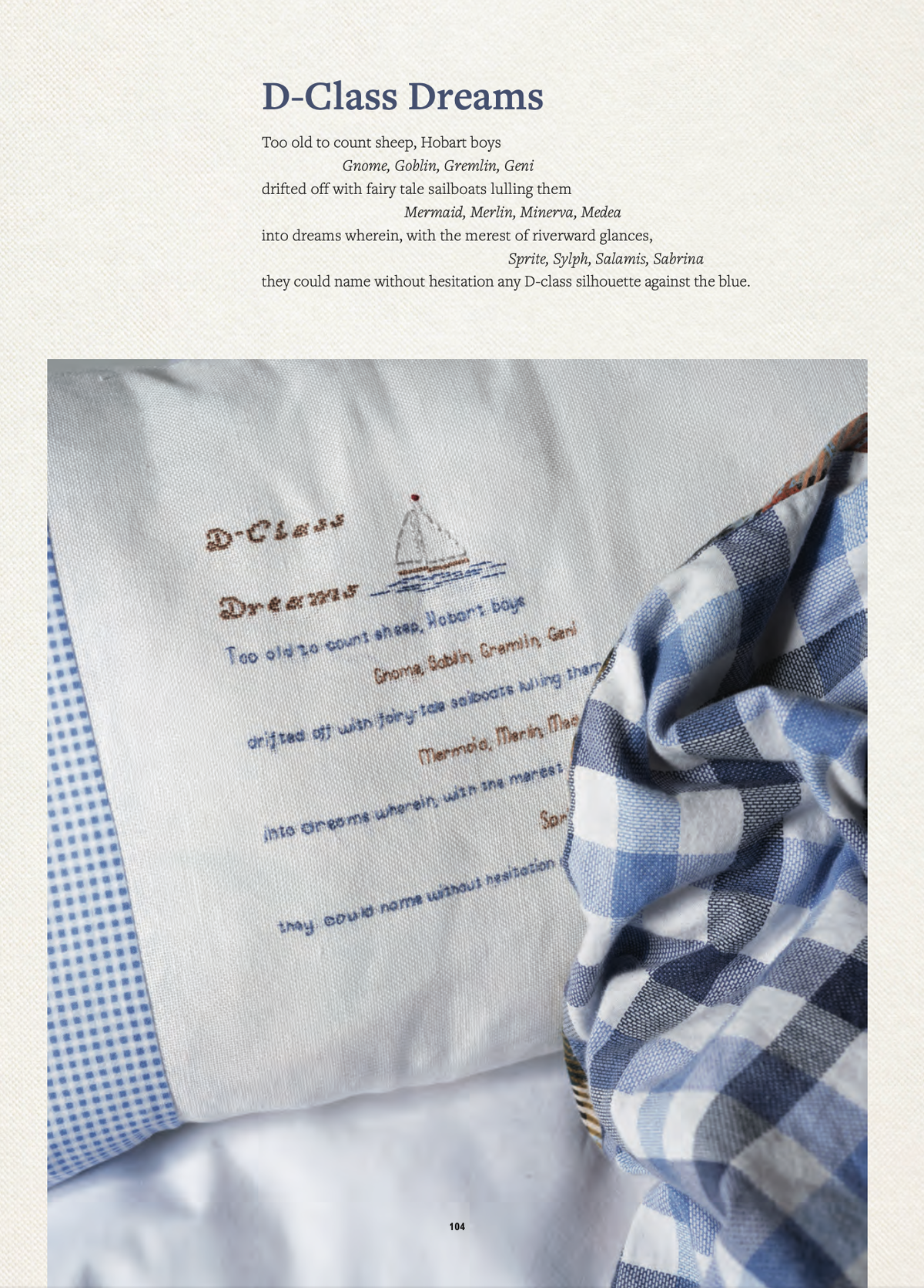

The textiles were not the only surprise of the residency, however. I think it was because I was having so much fun - poking around in the storerooms, drifting around the galleries - that I forgot my fear of line-endings. Thus, a couple of the pieces published in Island 164 look like (actually are?) real, honest-to-goodness poems. A very simple one is 'D-Class Dreams', which I both wrote, and embroidered onto a pillowslip. Impressed by a suite of bird poems by Tasmanian poet Louise Oxley, I also attempted the Korean verse form of the sijo in 'The Bowline's Sijo', a tiny little love poem to my favourite knot.

The stitching, the line-endings ... these little artistic departures illustrate the liberating capacity of residencies. At the Maritime Museum of Tasmania, I had the opportunity to play, stepping out of my comfort zone to experiment with materials, techniques and genres.

I am grateful to the assistant curator Annalise Rees, whose creativity gave licence to mine, and to all the staff and volunteers at the museum, whose knowledge and generosity helped so much, and to the Hobart City Council, for its generous funding of the residency program. Thanks, too, to the team at Island for sharing this work in that magazine's august pages.'