31 August 2022

Column from The Mercury, August 5, 2022

It’s a bittersweet week for those who love the wild places of this island. While forest protesters in takayna/Tarkine are celebrating a reprieve from the immediate threat of a toxic mine tailings dump being dug into the north-west rainforest, in Hobart a series of arts events has been organised to honour Lake Pedder, lost 50 years ago in one the worst acts of environmental destruction in the state’s history.

The confluence makes it an interesting moment in which to pause and think about the nature, and importance, of protest.

The breathing space granted to takayna/Tarkine was delivered by Federal Court Justice Mark Moshinsky, who ordered the machinery of majority Chinese-owned mining company MMG be removed pending deeper consideration of their project’s impact on the endangered Tasmanian masked owl. But this outcome could not have been achieved without the vigilance and determination of protesters.

Direct action gets a lot of attention, but in takayna/Tarkine, it’s only ever been only part of the campaign story. The less visible efforts to protect the region, with its natural values and immense significance to Tasmania’s first nations people, have included generating awareness, political lobbying, letter writing and the mounting of legal challenges.

But while that work was going on, on-the-ground protesters provided protection to the forest for nineteen months in the form of blockades and daily actions. They effectively kept intact land that would have been laid to waste even while the justice system was catching up to reality on its slow-turning wheels.

Ironically, while debate around the State Government’s anti-protest laws (still to pass the Upper House) has given policing authorities crystal-clear guidance on how to treat protesters in takayna/Tarkine, there hasn’t appeared to be anyone who felt they had the jurisdiction to police the legality of actions undertaken by the mining company. Without the protesters to keep watch, it’s doubtful anyone much would even have known that MMG was about the destroy a chunk of habitat belonging to an iconic and endangered bird, let alone acted upon that knowledge.

MMG seems set on locating its tailings dump right in takayna/Tarkine. The Bob Brown Foundation, however, argues that there are alternatives: a tailings dump could be located outside takayna/Tarkine, or else an alternative method of processing the mine’s waste could be utilised.

With a twinge of déjà vu, we could observe that Pedder, drowned as part of a hydro-electric power scheme, could have been saved if Tasmania’s state government accepted a multi-million dollar offer by the Prime Minister of the day, Gough Whitlam, to enable an alternative scheme – one that would have preserved the lake.

While the fight to preserve Lake Pedder proved galvanizing for the nascent environmental movement of the late 1960s, and led to the formation of the world’s first green political party in the shape of the United Tasmania Group, that campaign was not characterised by direct action.

The prevailing belief of the ‘Pedder People’ seems to have been that if they protested according to the rules, wrote persuasive letters to the right people, got enough signatures on petitions, and consistently drew attention to the laws that ought to have protected the lake at the heart of a National Park, they would win their struggle. But due process failed them, and the lake was lost.

Kevin Kiernan, a scientist who fought for the lake, has described one of the legacies of the loss as ‘an unwanted cynicism’, a sentiment echoed by many of the ‘Pedder people’, who feel that with the drowning of the lake, they lost not only a natural treasure, but also their faith in the structures that underpinned their society.

By the time the fight for the Franklin River began in the 1980s, activists knew they were beyond restraint. They believed direct action had to be part of the picture, or they would likely lose again. They were right.

Had the letters and petitions, lobbying and awareness raising of the ‘Pedder People’ of the late 1960s and early 1970s been heeded, we might have avoided the destruction of one of the most beautiful places on earth.

Still, it is a place that refuses to be forgotten, and hopes remain for its eventual restoration.

Last night at the State Cinema, there screened a photographic essay of black and white images taken by the late Geoff Parr – artist and arts educator – who documented the last days of the true lake, and the beginnings of the fake one, in a series of stunning and heart-breaking images.

His Pedder pictures, taken in 1973, spent decades in storage, but were rediscovered last year by Parr’s partner, the artist Pat Brassington, and by Tracey Diggins and Lynda Warner of Outside the Box/Earth Arts Rights, who recognised their profound significance and, eventually, combined them to create a cinematic experience.

Parr did see the lake with his own eyes, but there exists now a new generation of artists who care about Lake Pedder even though they have only ever seen it through the eyes of the artists, photographers, writers and activists who came before them.

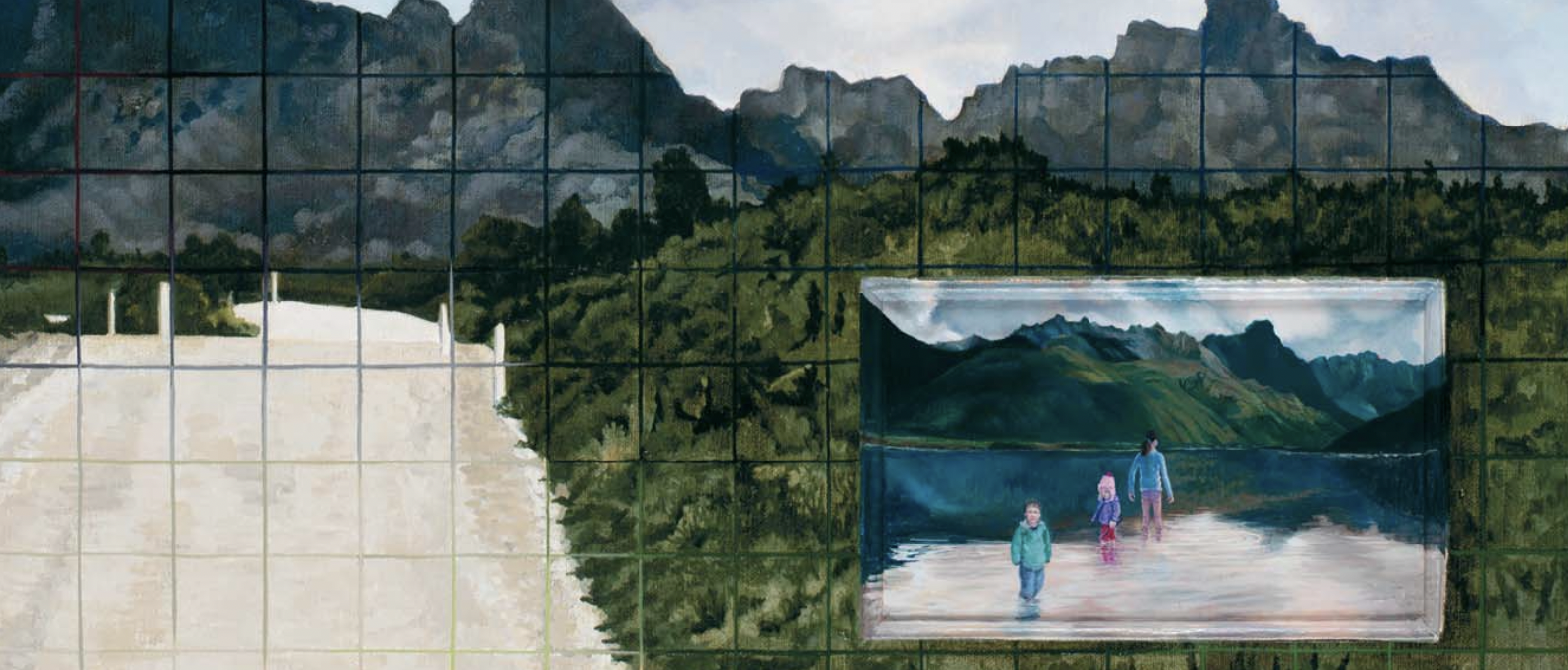

Proof of this will be on display at the Bett Gallery from tomorrow, when the exhibition ‘water[shed]’ will open, showcasing works by almost 50 artists, sufficiently moved by their real or inherited memories of Lake Pedder to make art about its history. And its future.

‘The Lake,’ writes Tracey Diggins, ‘is the actual and symbolic heart of lutruwita [Tasmania]. Restoring the Lake is the perfect Australian flagship project for this Unit Nations Decade on Ecosystem Restoration 2021-2030 that we are now in.’

It’s important to remember that the reprieve in takayna/Tarkine is only temporary.

Come 2072, will we be talking about trying to restore the rainforest to its former splendour? Or will we be proud that we paid attention to the vision of protesters from 50 years earlier, and saved it from destruction?